Innovation Bubbles

Trouble in (b)la-(b)la land.

Last week one of my portfolio companies (UIB, a globally leading conversational AI and IoT Holding based out of Singapore) won1 Acquisition International’s 2023 Global Excellence Award as the Most Innovative IoT Messaging Solutions Company.

I’m always happy when my team at UIB brings home these awards, even if we’ve won a ton of them over the years already. Unfortunately, real innovation is seldom realized by those who both could and would truly take it to market.

Intellectual innovation is of course clearly visible to IP lawyers and consultants, the professionals working at patent offices and intelligent researchers and analysts looking at future trends and key players in those markets whom they correctly identify.

On the other hand traditional procurement (which is typically trained to buy what’s already out there for the best value) has a hard time “buying disruptive innovation” as it’s not available right of the shelves. Many times it’s also just that a simple “order code” is missing in the IT system. Yes, really — I experienced this many times!

The opportunities to partner, buy or co-create something new and better then sadly get passed on to so-called “innovation teams” who often do not understand either but there then the innovation stands at risk to get manipulated, copied, misused or simply get lost, especially in larger organizations.

Despite being in a position to find, manifest and monetize new ideas, those innovation teams are at permanent war with their own ego’s and the corporate structures and processes they have to follow and by which otherwise successful innovation outcomes are mostly buried.

Thus the fertile grounds for trying something new become ground zero for frustrations, burned bridges and big losses of capital (both in intellectual as well as in monetary value) for all those involved in the process of “Collaborative Innovation”.

I speak from experience and will give a few examples at the end of this article. Meanwhile, what does one of the top innovators and Polymaths of the last century have to say about the emergency of new ideas?

“My ideas have undergone a process of emergence by emergency. When they are needed badly enough, they are accepted.” — Buckminster Fuller2

The Global Innovation Index

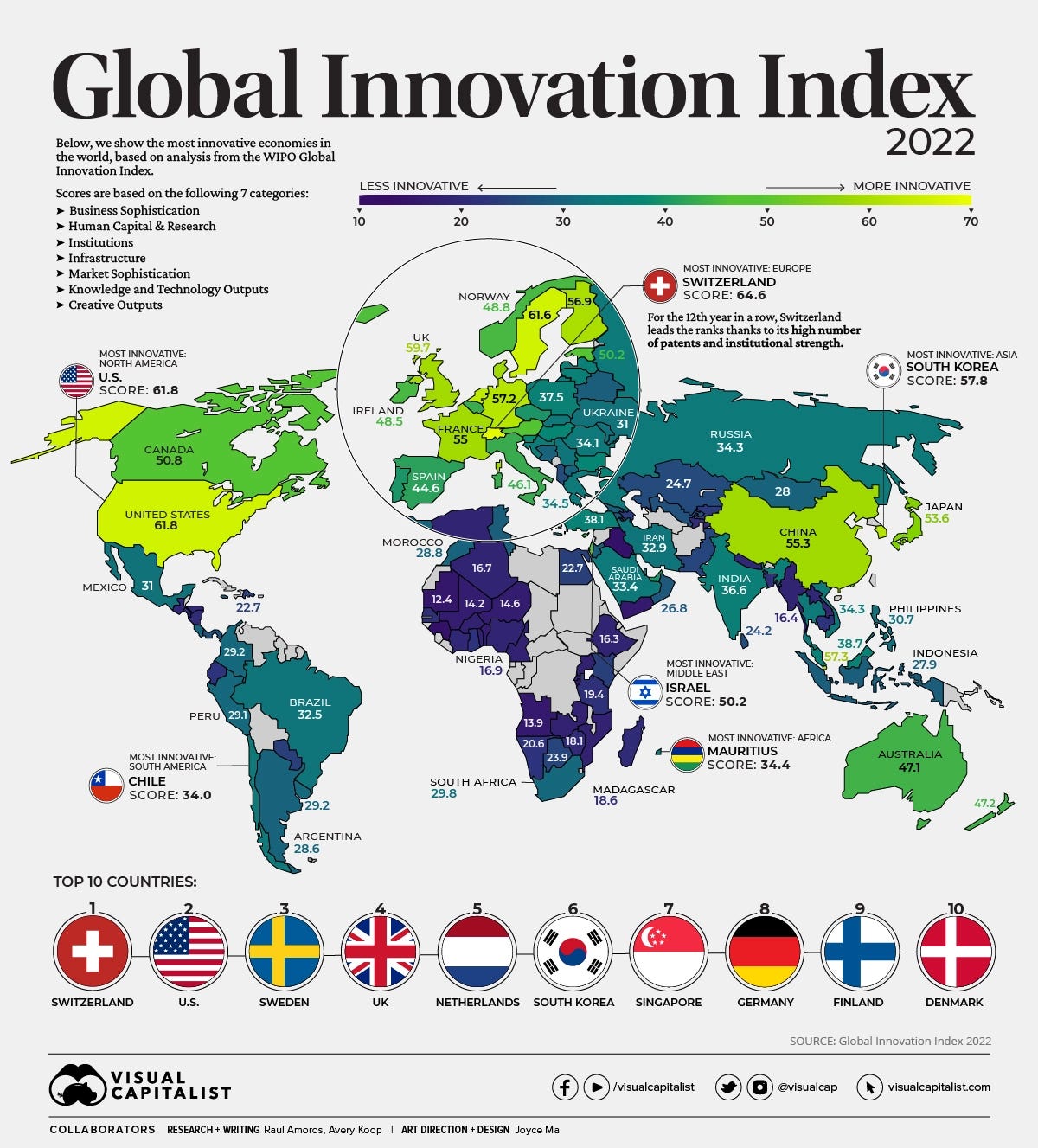

In its 15th edition now, WIPO’s Global Innovation Report for 20223 gives good insights as to where innovation happens in the world — at least from one of the more tangible ways to measure it, i.e. in the form of patent filings.

The data shows Switzerland and the US as still being on top, but if you take a look at the actual report and the developments in 2023, you will find that in particular BRICS4 states such as India or China are heavily investing in both IP documented innovation as well as in less measurable idea capital — which nevertheless forms the basis for a country’s overall innovation potential by extrapolating future earnings in GDP contributing to long term value creation and the respective innovation wealth and resilience in a nation.

The problem with using patent filings as the main indicator to perceive a “State of Global Innovation” is that it overlooks many key drivers responsible for the success or failure of a new idea possibly hitting the markets. An idea’s “acceptance speed” for instance, is a major factor which ignores all rules.

Also, nowadays we have to be careful whether the idea was even human-originated, or, AI-made. Even then, how to determine it’s underlying intellectual capital onwership and monetary value? And if it’s possible — how to use it for finance and share the value among a group of friends, co-inventors or collaborators in a transparent and fair way?

What's Intellectual Capital?

Listen now (39 min) | Welcome to the first episode of “Toby & Friends” — the virtual campfire for knowledge sharing! “If you’re the smartest person in the room, you’re in the wrong room” — Confucius The purpose of this podcast is to share knowledge with friends. No agenda. No sponsors. Just coming up with solutions to the most pressing problems of our Modern Times.

“Buerocrazy” Kills Innovation

I’ve found this story on LinkedIn quite a while ago and unfortunately missed to copy the author’s name (if anyone finds, please let me know and I will properly attribute). Nevertheless, this story is so good that I didn’t want you to miss it as it also shows the trouble with innovation when you’re not sure of the origin of an idea (or story, as in this case), so here it goes:

The US standard track gauge is 4 feet 8.5 inches, because that's how they were built in England. Being in a new land, why did the English engineers not design the first US railroad lines different?

Because the first railways were built by the same people who built the trams, and they used the gauge which was used by the people who built the streetcars who used the same jigs and tools that they had used to build cars that had the same wheelbase.

Then why did the wagons have this special wheel spacing? If one had tried to use a different wheel spacing, wagon wheels would have broken more frequently on some of the old trunk roads in England. This is the distance between the ruts.

So who built these old rutted roads? Imperial Rome built the first trunk roads in Europe (including England) for its legions. These roads have been used ever since. And what about the ruts on the roads? Roman war chariots made the first ruts that everyone else had to conform to or risk destroying their chariot wheels. Since the chariots were built for Imperial Rome, they were all the same in terms of wheel spacing.

Thus, the United States standard track gauge of 4 feet 8.5 inches is derived from the original specifications for an Imperial Roman war chariot. Bureaucracies live forever.

So when you're presented with a specification/procedure/process and you're wondering, "What idiot thought of that?" you might be spot on. The chariots of the Imperial Roman army were just wide enough to accommodate the hind quarters of two war horses!

And to make is final point, the author goes on further saying:

When you see a space shuttle sitting on its launch pad, there are two large booster rockets attached to the sides of the main tank. These are the Solid Rocket Boosters, or SRBs for short. The SRBs are manufactured by Thiokol at their Utah facility. The engineers who designed the SRBs would have preferred to make them a little thicker, but the SRBs had to be transported from the factory to the launch site by train. The rail line from the factory happens to go through a tunnel in the mountains, and the SRBs had to fit through that tunnel. The tunnel is a little wider than the railroad track, and the railroad track, as you know, is about the width of two horses' butts.

So a key design feature of the Space Shuttle, arguably the world's most advanced transportation system, was determined more than two thousand years ago by the width of a horse's butt…

Can you imagine how many times the world of innovation today is limited (or more often) killed by buerocracy?

Scratch Your Own Itch

Ted Merz5 recently shared a nice story from his days at Bloomberg on his LinkedIn Feed covering the birth of one of Bloomberg’s most valuable innovations. It goes like this:

Bloomberg’s most valuable application wasn’t proposed by senior management or product managers. It wasn’t part of a strategic plan. It wasn’t conceived as a killer app. It was pitched and built by engineers working on an unrelated project.

Bloomberg Message (and its offspring, Instant Bloomberg) is the moat around the company’s business. It allows 330,000 clients in the platform’s gated community to communicate.

In the early 1990s, New York-based engineers were working with colleagues in London on a foreign exchange application. The group set up a bulletin board where people could type in a question and hope someone across the pond would see it and respond. Aside from not knowing when the message might be seen, the specific question was folded into a general flow of chatter about unrelated topics.

“It was a horrendous way to communicate,” one engineer recounted.

The engineers wrote code to create a database that stored the text and sent out a notification every time someone logged in. That laid the groundwork for one-to-one communication. The engineers wanted to release the application to clients. They pitched it to Mike Bloomberg who was skeptical.“Does anyone need that? Would people use it?”

The engineers offered to forgo compensation if they were paid one penny per message. Mike said that if they had that much conviction they should go ahead.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the product they rolled out changed the fortunes of the company and as a result the landscape of global finance.

No customers asked for this feature. There was no focus group or UX review, no survey of the total addressable market or prediction of usage. No one said: “Let’s establish baseline metrics to measure what success looks like.”

Engineers saw the need and wrote the code.

In a world that stresses process over product and user counts over usability, it’s a powerful reminder of how leaps in innovation often emerge organically.

Innovation bubbles end where you can personally start to experience the value of your idea. Alternatively, if you are so convinced of the positive results from your innovation in action that you’re willing to forgo compensation and work on a pure success basis, you at least followed your belief to a point of conclusion, not having to wonder for the rest of your life: what if? — Toby Ruckert

The Pitfalls of Innovation

In my professional life I have experienced many ways how innovation can fail, here are some examples and what you can do about them: